Cold War Espionage Uncovered: Secrets, Spies and Silent Wars

Cold War espionage was more than just a battle of spies—it was a silent war waged in the shadows of diplomacy, nuclear threats, and ideological rivalry. From hidden microphones in embassies to double agents passing state secrets, the struggle between the East and West was fueled not only by weapons but by information.

In an era where open conflict risked global annihilation, covert operations, intelligence warfare, and spycraft became the preferred weapons of both superpowers. Agencies like the CIA and the KGB operated behind closed doors, manipulating governments, infiltrating movements, and influencing the very course of 20th-century history.

This article delves into the secret world of Cold War spies, exposing how unseen hands shaped visible outcomes—and how espionage defined the Cold War as much as any arms race or battlefield. If u are interested in proxy wars in cold war you might want to see this article:

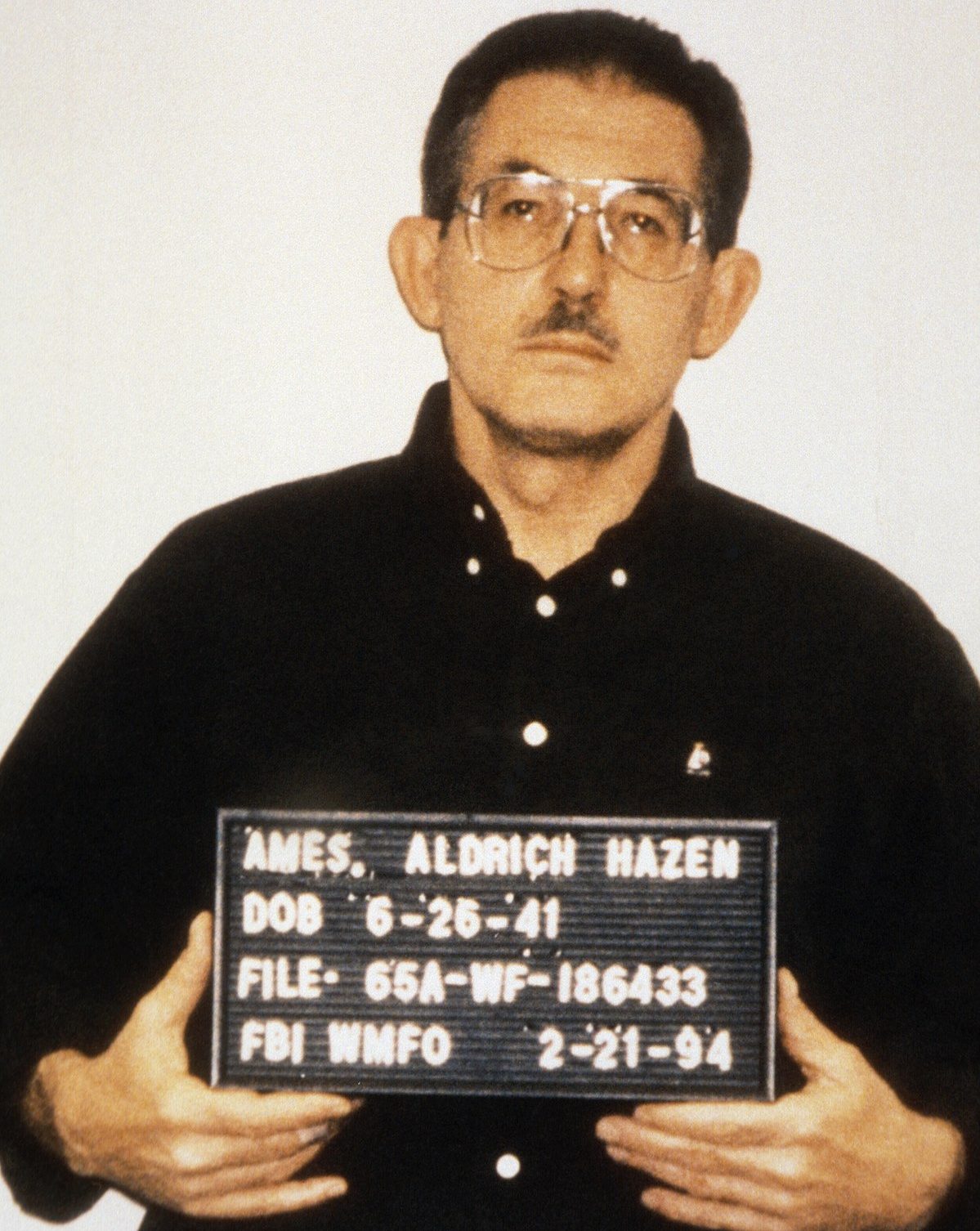

Cold War Espionage – The Double Life of Aldrich Ames

Operating from within the very heart of the U.S. intelligence community, Ames’s betrayal began in 1985, at the height of Cold War tension. His motives? Not ideology—but money. In exchange for over 2.5 million dollars, the KGB received the names of key American informants inside the USSR, many of whom were later executed.

What made Ames’s case particularly alarming was the depth of infiltration—a reminder of how Cold War spycraft often blurred the lines between patriotism and personal gain. His eventual arrest in 1994 was a wake-up call for U.S. counterintelligence and led to massive internal reforms.

The Ames affair stands as a chilling example of how one insider, driven by greed, could inflict damage that no army could achieve—and how Cold War espionage was sometimes fought not on foreign soil, but from inside American offices.

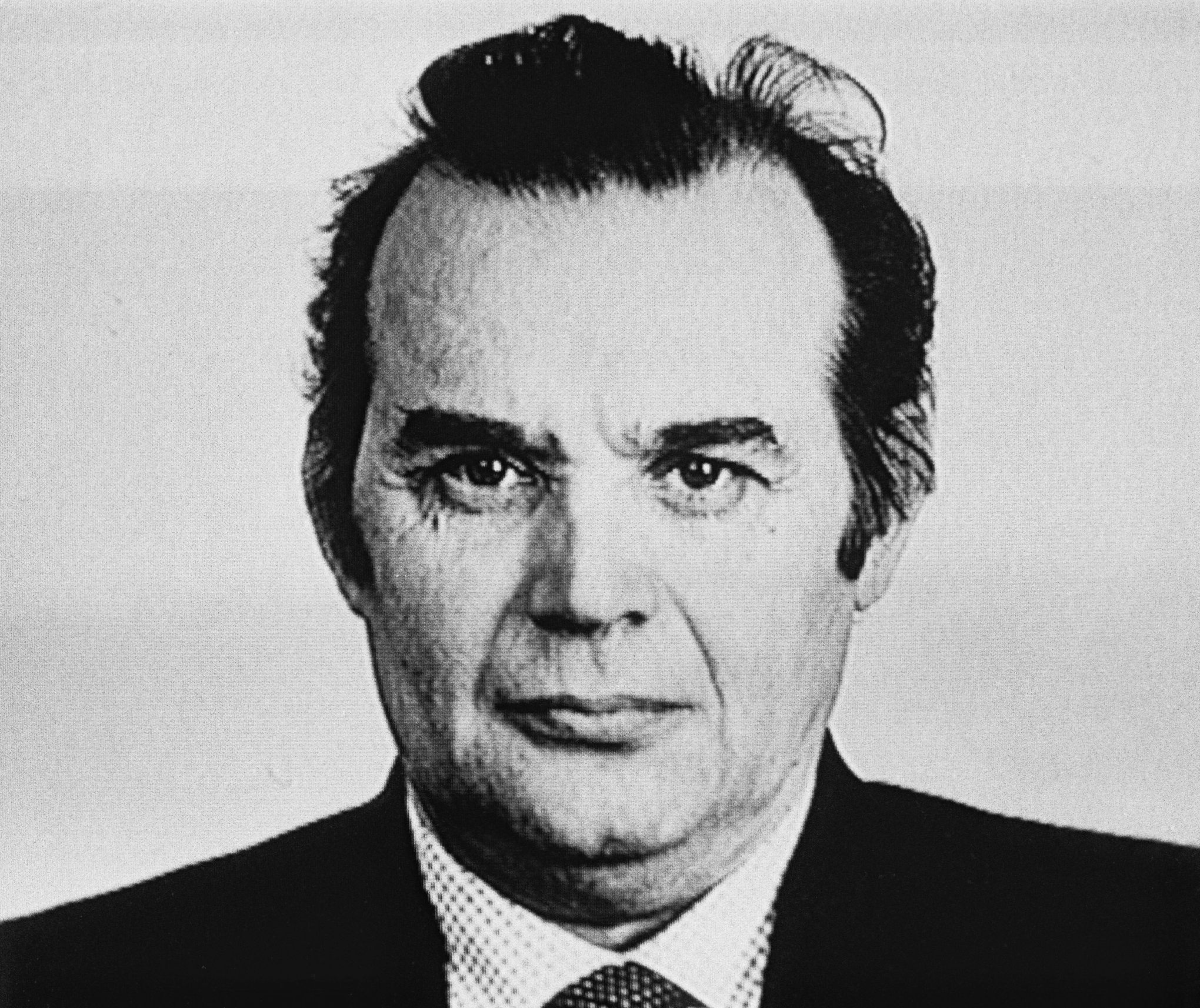

Cold War Espionage – The Betrayal of the Cambridge Five

Among the most infamous espionage networks of the 20th century, the Cambridge Five shocked the Western world with their long-standing betrayal. These five British intelligence officers—Kim Philby, Guy Burgess, Donald Maclean, Anthony Blunt, and possibly John Cairncross—were secretly working for the Soviet Union.

Recruited during their university days at Cambridge in the 1930s, the group rose through the ranks of British intelligence and diplomatic services. For years, they passed classified information to the KGB, undermining countless Allied operations during the Cold War.

Philby, perhaps the most well-known of the five, infiltrated MI6 and even collaborated with CIA agents, all while feeding sensitive intel directly to Moscow. Their betrayal wasn’t uncovered until the 1950s and 60s, causing a massive loss of trust between British and American intelligence.

The Cambridge Five embody the ideological side of Cold War espionage—unlike Ames, these men weren’t motivated by money, but by communist loyalty. Their actions not only damaged Allied efforts but also eroded internal confidence, proving that Cold War spy networks could be built on belief rather than bribes.

Operation Gold – The Cold War Espionage Tunnel Beneath Berlin

Not all cold war espionage stories involved double agents or defections—some were feats of sheer technical audacity. One of the most daring was Operation Gold, a covert collaboration between the CIA and MI6 during the 1950s. The mission: to tap into Soviet communications by digging a tunnel beneath East Berlin.

Stretching over 1,500 feet, the tunnel aimed to intercept key telephone lines used by Soviet military and intelligence leaders. It was a bold move in the silent intelligence war between superpowers.

However, the operation was compromised from the very start. British double agent George Blake, secretly working for the KGB, had already informed the Soviets. Curiously, they allowed the tunnel to remain active for nearly a year—likely to protect Blake’s identity and feed false intel.

Operation Gold remains a fascinating case of Cold War surveillance, showcasing the extremes both sides reached to outmaneuver one another—even beneath the ground.

The Farewell Dossier – When France Exposed Soviet Spies

One of the most strategic and lesser-known operations in Cold War espionage history unfolded in the early 1980s, when French intelligence received a shocking revelation from within the Soviet ranks.

Vladimir Vetrov, a KGB officer disillusioned with the regime, secretly passed over 4,000 documents to the French, identifying hundreds of Soviet agents operating in the West. This leak, later dubbed the Farewell Dossier, exposed the extent of Soviet industrial and technological espionage against NATO countries.

The intelligence was shared with the U.S., leading to a large-scale counterintelligence crackdown. As a direct consequence, the West fed the KGB flawed data that sabotaged Soviet research and technology for years.

The Farewell Dossier wasn’t just a massive intelligence win—it was a turning point that helped undermine the Soviet Union’s technological ambitions during the final decade of the Cold War.

Cold War Espionage: The Chilling Case of Navy Spy John Anthony Walker

Among the darkest chapters of Cold War espionage, few cases rival the impact of John Anthony Walker, a U.S. Navy officer turned Soviet informant. Between 1967 and 1985, Walker ran one of the most destructive spy rings of the entire conflict, selling top-secret naval communications to the KGB.

What set this espionage case apart was not just the scale, but the deep level of infiltration. By providing encryption keys and classified codes, Walker enabled the Soviet Union to read over a million U.S. Navy messages—seriously jeopardizing American military strategy.

The damage inflicted by Walker’s betrayal forced the U.S. to completely overhaul its cryptographic systems. His arrest in 1985 finally ended this long-running operation, but the consequences rippled through the intelligence community for years.